Alaska’s 500-Quake Week Exposes Tsunami Warning System Funding Crisis

- Sami El-Amin

- 28 November 2025

- 0 Comments

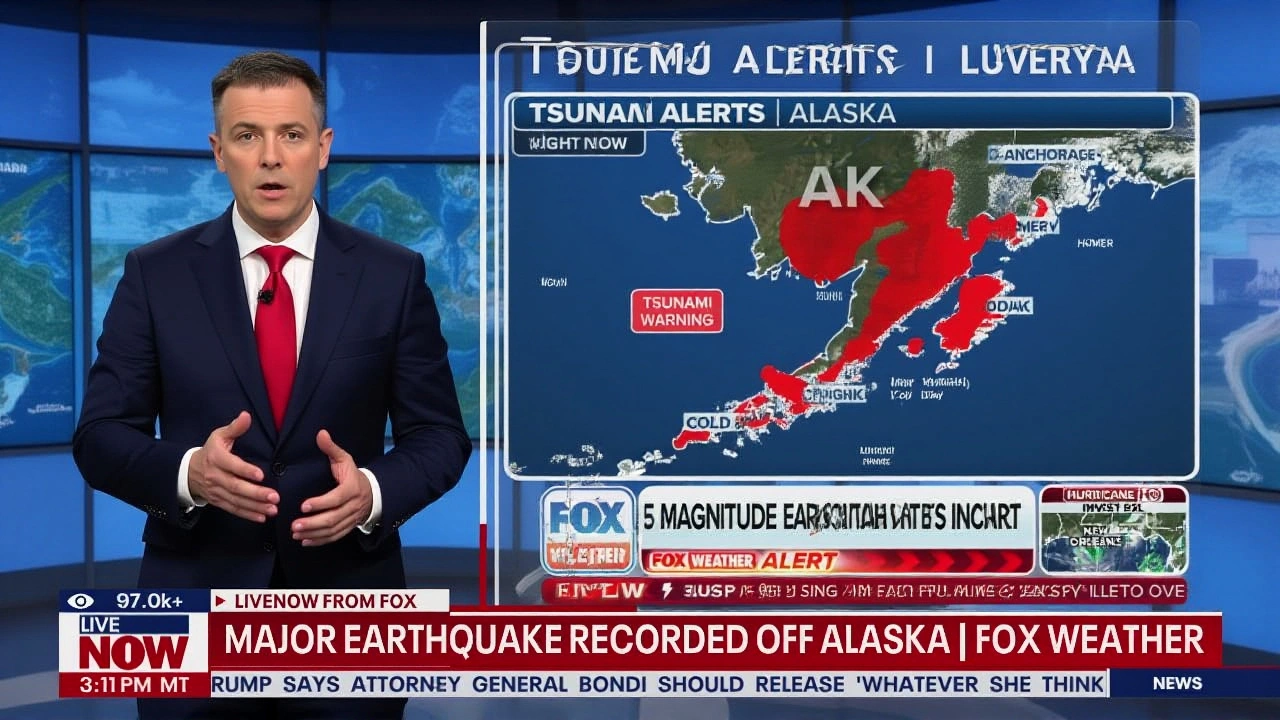

A magnitude 6.0 earthquake rattled southern Alaska just before 9 a.m. local time on Thanksgiving Day, November 27, 2025, shaking buildings in Anchorage and triggering a flood of reports from more than 6,300 residents to the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The quake, centered 14 kilometers west of Susitna at a depth of 80.4 kilometers, was the latest in a staggering sequence of nearly 500 tremors that struck the state over the previous week — including a magnitude 5.8 quake west of Adak on November 22. Despite the intensity, no damage or injuries were reported. But behind the calm aftermath lies a far more dangerous story: NOAA has cut $300,000 in annual funding to the Alaska Earthquake Center (AEC), threatening to silence nine critical seismic monitors by the end of November — just as Alaska’s quake activity hits a modern peak.

When the Ground Shakes, But the Warnings Might Not

The Anchorage quake was strong enough to rattle coffee cups and send people into the streets, yet it triggered no tsunami alert. That’s because the National Tsunami Warning Center confirmed early on that the quake’s depth and location posed no ocean-displacing risk. But here’s the twist: even if the next one does, the system might not respond in time. That’s because NOAA quietly canceled its $300,000 grant to the Alaska Earthquake Center in Fairbanks on November 19, 2025 — a decision that will force nine of its own seismic stations across Alaska to go dark by month’s end.Don’t mistake this for a technical glitch. These aren’t backup sensors. They’re the direct, real-time feed to the tsunami warning network. Without them, data from the Aleutian Islands — where the Pacific Plate dives beneath North America — could be delayed by hours. And in a region where a Cascadia Subduction Zone quake could send a wall of water crashing into Washington’s coast in as little as 15 minutes, delays aren’t just inconvenient — they’re deadly.

Senator Cantwell’s Warning: A System on the Brink

Maria Cantwell, the Democratic Ranking Member of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, didn’t wait for the next disaster to speak up. On November 19, she sent a blistering letter to NOAA Administrator Neil Jacobs, demanding immediate answers. "NOAA must work to restore seismic information needed for tsunami alerts in Alaska," she wrote, "and develop a concrete plan to protect this data in other critical locations from going offline or being delayed." Her warning wasn’t theoretical. She pointed directly to the Cascadia Subduction Zone, the 700-mile fault off the Pacific Northwest coast that last ruptured in 1700 and is overdue for another massive quake. "A tsunami generated by Cascadia could hit communities in 15-30 minutes," she noted. "Any potential delays in life-saving information puts our communities at risk." The irony? The Alaska Earthquake Center still operates 250 other seismic stations across the state — many of them funded by the state itself after the federal cut. But those stations don’t feed directly into NOAA’s tsunami alert system. They’re used for scientific analysis and local hazard mapping. The nine canceled stations? They’re the ones wired into the national emergency network.Why Alaska? Because It’s Ground Zero for Earthquakes

Alaska isn’t just earthquake-prone — it’s the epicenter of U.S. seismic activity. The state records more quakes than all other 49 states combined. The 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake in Prince William Sound, a 9.2-magnitude monster, remains the second-strongest ever recorded on Earth. It triggered a tsunami that killed 131 people across Alaska, Oregon, and California. Since then, Alaska’s monitoring network has been the gold standard. But funding has been patchy. The Alaska Seismic Hazards Safety Commission has repeatedly warned that the state’s infrastructure — roads, bridges, pipelines — remains vulnerable, especially in rural areas. Now, with the federal cuts, even the early warning layer is at risk.

What’s Next? A Race Against Time

The Alaska Earthquake Center has temporarily backfilled the funding gap using state resources, ensuring tsunami alerts for the West Coast remain operational — for now. But that’s a stopgap, not a solution. The nine NOAA stations are scheduled to shut down by November 30, 2025. There’s no public timeline for restoring the funds. Meanwhile, the seismic activity shows no sign of slowing. The nearly 500 quakes in the past week? Only five were felt by people. That’s the scary part. Most earthquakes are silent. But the next one — the one that could trigger a tsunami — won’t be. And if the sensors are offline, no one will hear it coming.Why This Matters to Everyone on the West Coast

This isn’t just Alaska’s problem. Tsunami warnings from Alaska’s coast travel south — to British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and even northern California. A delay in detection means less time for evacuation. In coastal towns like Seaside, Oregon or Hoonah, Alaska, minutes matter. People don’t have cars. They don’t have highways. They have hills — and time. The NOAA cut came as part of broader budget reallocations. But in a world where climate change is increasing ocean instability and tectonic stress is building, turning off the alarms isn’t fiscal responsibility — it’s gambling with lives.Frequently Asked Questions

How does the cancellation of $300,000 in funding affect tsunami warnings for the U.S. West Coast?

The cut disables nine NOAA-run seismic stations in Alaska that provide real-time data directly to the National Tsunami Warning Center. While the Alaska Earthquake Center’s 250 other stations still detect quakes, their data flows through slower, non-emergency channels. This could delay tsunami alerts by hours — a critical gap when a Cascadia quake could send a wave to Washington’s coast in under 30 minutes.

Why are only five of the nearly 500 earthquakes felt by residents?

Most Alaska earthquakes are small, deep, or occur in remote areas like the Aleutian Islands. The human perception threshold is typically above magnitude 3.0 and near populated zones. The recent 6.0 quake near Anchorage was unusual in its visibility — most tremors are too faint or too far away to be noticed without instruments.

What happened during the 1964 Alaska earthquake, and why is it relevant today?

The 9.2-magnitude 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake in Prince William Sound remains the second-strongest ever recorded. It triggered a tsunami that killed 131 people across the Pacific, including in California. It also exposed how unprepared the U.S. was for such events — leading to the creation of today’s tsunami warning system. Without modern monitoring, a repeat could be far deadlier.

Is there any chance the funding will be restored before the stations shut down?

As of late November 2025, no formal plan or timeline for restoring the $300,000 has been announced by NOAA. Senator Cantwell has demanded answers, but Congress is not currently in session. The Alaska Earthquake Center is using state funds as a temporary fix, but that’s unsustainable long-term without federal support.

How does the Cascadia Subduction Zone relate to Alaska’s seismic activity?

Though Cascadia lies off the Pacific Northwest, its tsunami risk depends on early detection from Alaska’s seismic network. The same tectonic forces that cause Alaska’s quakes also drive Cascadia’s buildup. If Alaska’s sensors go offline, the first warning of a Cascadia rupture may come too late — even if the quake happens 1,000 miles away.

What can citizens do to push for action?

Residents of coastal states can contact their congressional representatives to demand restoration of NOAA’s funding for Alaska’s seismic network. Public pressure has reversed similar cuts before — like the 2018 funding restoration for West Coast tsunami buoys. Awareness is the first step to preventing a preventable tragedy.